Big data, agent-based modelling, and smart cities: A triumvirate to rival Rome?

This is a longer version of a contribution made to the following article:

Harris, Richard, David O’Sullivan, Mark Gahegan, Martin Charlton, Lex Comber, Paul Longley, Chris Brunsdon, Nick Malleson, Alison Heppenstall, Alex Single- ton, Daniel Arribas-Bel, Andy Evans (2017). More bark than bytes? Reflections on 21+ years of geocomputation. Environment and Planning B: Urban Analytics and City Science 44 (4) 598–617. DOI: 10.1177/2399808317710132.

Following the Big Data “revolution” (Mayer-Schunberger and Cukier, 2013), high-resolution, individual-data are everywhere. Aspects of peoples lives that have never before been documented, let-alone digitised and archived, are being captured and analysed overtly and covertly through our use of smart-phone applications, social media contributions (Croitoru et al., 2013; Malleson and Andresen, 2015), public transport smart cards (Batty et al., 2013), mobile telephone activity (Diao et al., 2016), credit/debit card transactions, web browsing history, etc., etc. These personal data are being supplemented with sensed data about the physical environment (air quality, temperature, noise, etc.) as well as with aggregate sources such as pedestrian footfall or vehicle counters (Bond and Kanaan, 2015). Taken together, the data provide a wealth of current information about the world, especially in cities. This “data deluge” (Kitchin, 2013) has spawned interest in ‘smart cities’; a term that is commonly used to refer to cities that “are increasingly composed of and monitored by pervasive and ubiquitous computing and, on the other, whose economy and governance is being driven by innovation, creativity and entrepreneurship, enacted by smart people” (Kitchin, 2014).

The motivation for smart cities is clear. By 2050, the United Nations predicts that 66% of the world’s population will live in urban areas. Providing sufficient services such as housing, energy, waste disposal, healthcare, transportation, education and employment will be extremely challenging. Therefore a clearer understanding of urban dynamics, that ‘smart cities’ can potentially offer, is an attractive proposition. Indeed, ‘smart’ city initiatives are already emerging throughout the world (for examples see Kitchin (2014); Geertman et al. (2015)).

One aspect to many smart cities, that is largely absent in the published literature, is the ability to forecast as well as react. Whilst most initiatives inject real-time data, these data are rarely used to make real-time predictions about the future. Where ‘forecasting’ is an advertised capability of a smart city initiative, it is rarely explained in any detail. This might be due to the proprietary nature of many initiatives, which are often designed and implemented by corporations rather public bodies, but it is equally likely that a lack of appropriate methods is at fault. Although ‘black box’ artificial intelligence methods are progressing rapidly – for example neural networks are being used to: predict future frames in a video; create literature or paintings in the style of an artist; and even to drive autonomous cars – there is little evidence that these are being used to forecast future states of smart cities.

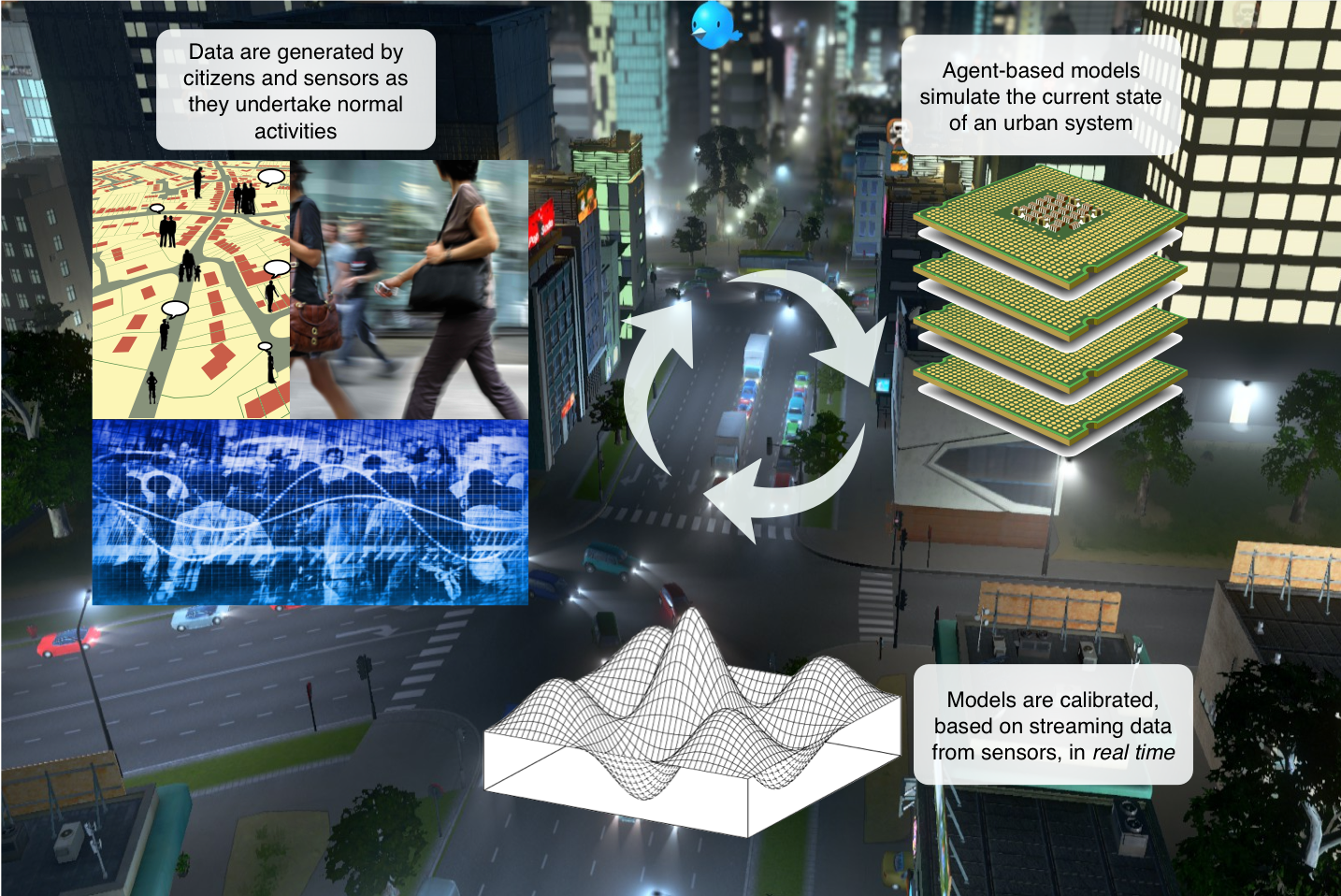

Instead, perhaps agent-based modelling offers the missing component for predictive smart cities. Agent-based models (ABMs) simulate the behaviour of the individual components that drive system behaviour, so are ideally suited to modelling cities. A drawback with ABMs is that they require high-resolution, individual-level data to allow reliable calibration and validation, and traditionally these data have been hard to come by. However, in the age of the smart city, this is no longer the case. Furthermore, ABMs are not ‘black boxes’, the individual agents are imbued with behavioural frameworks that are (usually) based on sound behavioural theories. This makes it easier to properly dissect the models, as well as allowing a controller to manipulate the behaviour of the agents as might be required for a particular forecast. Therefore, an agent-based simulation that is capable of simulating a representative population of synthetic individuals and is calibrated in real-time from streaming ‘smart’ data might offer an ideal means of both representing the current state of urban systems and for creating short-term forecasts of future urban scenarios. This triumvirate of big data, agent-based modelling, and dynamic calibration has the potential to become the de facto tool for understanding and modelling urban systems. The Figure below illustrates this vision.

There are, however, substantial methodological challenges that must be met first. Although the means of assimilating current data into models is well established in fields such as meteorology (Kalnay, 2003; Bauer et al., 2015), efforts in the field of agent-baed modelling are much less well developed (Lloyd et al., 2016; Ward et al., 2016). Existing methods are intrinsic to their underlying models – typically systems of partial differential equations – and cannot easily be disassociated from them for use in ABM. Furthermore, there are serious ethical risks that must be taken into account. Whilst care must be taken over the use of individual-level data, and much is being written about this already, this is not necessarily the most serious problem. The data assimilation methods should operate effectively on aggregate data, so there is not an inherent need to track individuals nor store their personal, individual-level data once it has been aggregated. A potentially greater risk comes from the unknown biasses in the data. Engagement with smart devices is not homogeneous across the population, so there is the risk that those individuals who choose not to use ‘smart’ technology will be forgotten about in simulations and in ‘smart’ planning processes. Furthermore, simulations that are based on biassed data have the potential to increase biasses by presenting biassed results that are then used to influence policy. For example, PredPol is an extremely popular predictive policing tool that is being purchased by police forces across the globe in order to predict where future crimes are going to take place. However, policing data are already biassed towards particularly minorities as a result of where most policing activity already takes place, so the tool has the potential to further increase these biasses by sending more officers to areas that are already being heavily policed (Lum and Isaac, 2016). Any smart city modelling/forecasting tool must be able to mitigate against these risks.

To conclude, this paper has argued that although smart city initiatives are numerous, very few can evidence an ability to create reliable forecasts of future city states. However, advances in spatial methods that typically fall under the umbrella of ‘geocomputation’ have the potential to create reliable forecasts of urban dynamics under a variety of conditions. There are ethical issues that must be given serious consideration, especially in ensuring that simulations are not biassed towards particularly groups of people, but if conducted safely, the triumvirate of agent-based modelling, big data, and dynamic calibration is an extremely attractive combination.

References

Batty, M., E. Manley, R. Milton, and J. Reades (2013). Smart London. In S. Bell and J. Paskins (Eds.), Imagining the Future City: London 2062 (1 ed.)., pp. 31–40. Ubiquity Press.

Bauer, P., A. Thorpe, and G. Brunet (2015). The quiet revolution of numerical weather prediction. Nature 525(7567), 47–55.

Bond, R. and A. Kanaan (2015). MassDOT Real Time Traffic Management System. In S. Geertman, J. Ferreira, R. Goodspeed, and J. Stillwell (Eds.), Planning Support Systems and Smart Cities, pp. 471–488. Cham: Springer International Publishing.

Croitoru, A., A. Crooks, J. Radzikowski, and A. Stefanidis (2013). Geosocial gauge: a system prototype for knowledge discovery from social media.

International Journal of Geographical Information Science 27(12), 2483–2508. Diao, M., Y. Zhu, J. Ferreira, and C. Ratti (2016). Inferring individual daily activities from mobile phone traces: A Boston example. Environment and Planning B: Planning and Design 43(5), 920–940.

Geertman, S., J. Ferreira, R. Goodspeed, and J. Stillwell (Eds.) (2015). Planning Support Systems and Smart Cities. Lecture Notes in Geoinformation and Cartography. Cham: Springer International Publishing.

Kalnay, E. (2003). Atmospheric Modeling, Data Assimilation and Predictability. Cambridge University Press.

Kitchin, R. (2013). Big data and human geography Opportunities, challenges and risks. Dialogues in Human Geography 3(3), 262–267.

Kitchin, R. (2014). The real-time city? Big data and smart urbanism. GeoJournal 79(1), 1–14.

Lloyd, D. J. B., N. Santitissadeekorn, and M. B. Short (2016). Exploring data assimilation and forecasting issues for an urban crime model. European Journal of Applied Mathematics 27(Special Issue 03), 451–478.

Lum, K. and W. Isaac (2016, October). To predict and serve? Significance 13(5), 14–19.

Malleson, N. and M. A. Andresen (2015). The impact of using social media data in crime rate calculations: shifting hot spots and changing spatial patterns. Cartography and Geographic Information Science 42(2), 112–121.

Mayer-Schönberger, V. and K. Cukier (2013). Big Data: A Revolution That Will Transform How We Live, Work and Think. London, UK: John Murray.

Ward, J. A., A. J. Evans, and N. S. Malleson (2016). Dynamic calibration of agent-based models using data assimilation. Open Science 3(4).